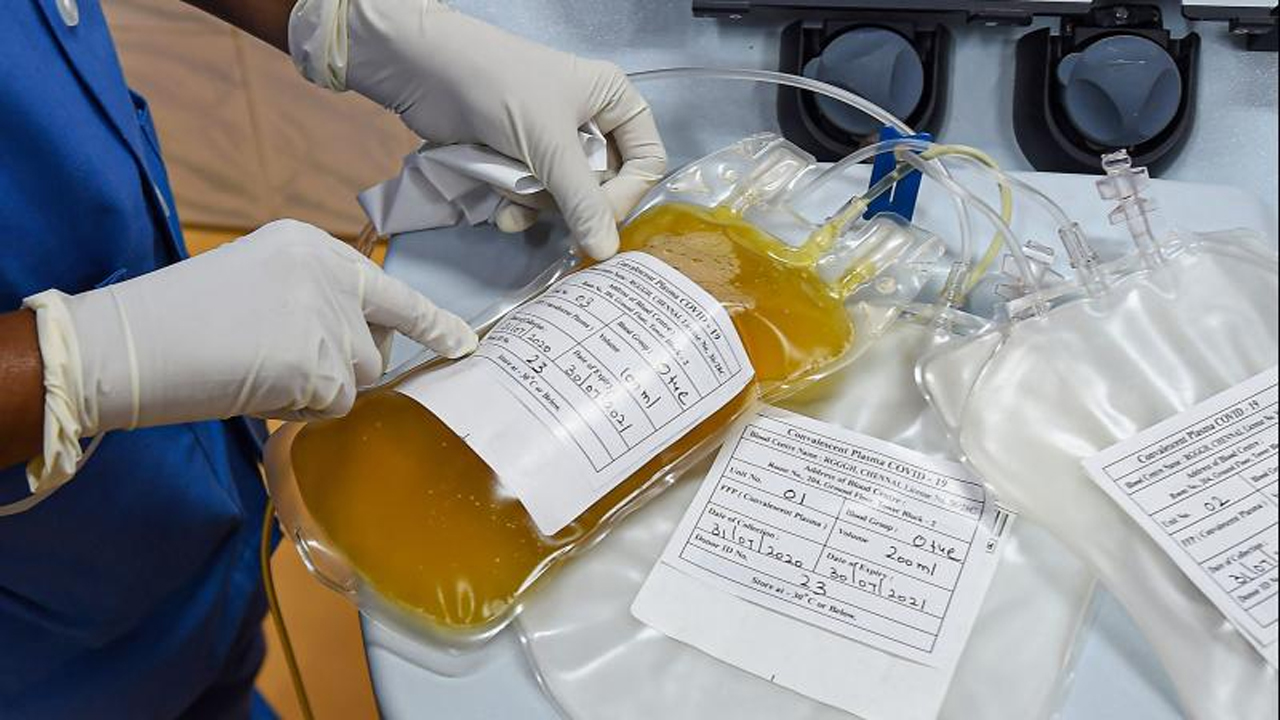

Researchers called on Friday for more research into using blood from recovered COVID-19 patients - or so-called convalescent plasma - as a potential treatment, after a small trial of hospitalised patients in India found it was of no benefit.

The Indian results, published in the BMJ British Medical Journal, found that the plasma, which delivers antibodies from COVID-19 survivors to infected people, did not help hospitalised patients fight off the infection, and failed to reduce death rates or halt progression to severe disease.

The findings are a setback for a potential therapy that U.S. President Donald Trump touted in August as a “historic breakthrough”, and one experts say has been used in some 100,000 patients in the United States already, despite limited evidence on its efficacy.

Scientists not directly involved in the India study, which involved around 460 patients, said its results were disappointing but should not mean doctors give up hope altogether on convalescent plasma.

They said further and larger trials are needed, including in COVID-19 patients with milder disease and those newly infected.

“With just a few hundred patients, (the India trial) is still much too small to give clear results,” said Martin Landray, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at Britain’s Oxford Universit.

“One could well imagine that the treatment might work particularly well in those earlier in the course of the disease or who have not been able to mount a good antibody response to the virus of their own,” he said. “But such speculation needs to be tested – we can’t just rely on an educated guess.”

While the United States and India have authorised convalescent plasma for emergency use, other countries, including Britain, are collecting donated plasma so that the treatment could be widely rolled out if it is shown to be effective.

The Indian researchers enrolled 464 adults with COVID-19 who were admitted to hospitals across India between April and July. They were randomly split into two groups - with one receiving two transfusions of convalescent plasma alongside best standard care, and the other getting best standard care only.

After seven days, use of convalescent plasma seemed to improve some symptoms, such as shortness of breath and fatigue, and led to higher rates of so-called negative conversion - a sign that the virus is being neutralised by antibodies.

But this did not translate into a reduction in deaths or progression to severe disease by 28 days.

Ian Jones, a Reading University professor of virology, agreed with Landray that plasma may be more likely to work very soon after someone contracts COVID-19.

He urged these and other researchers to continue to conduct trials, and to do so in newly diagnosed patients.

“We still do not have enough treatments for the early stage of disease to prevent severe disease and until this becomes an option, avoiding being infected with the virus remains the key message,” he said.

Article Source- Reuters.com

Researchers called on Friday for more research into using blood from recovered COVID-19 patients - or so-called convalescent plasma found it was of no benefit.

Researchers called on Friday for more research into using blood from recovered COVID-19 patients - or so-called convalescent plasma found it was of no benefit.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)