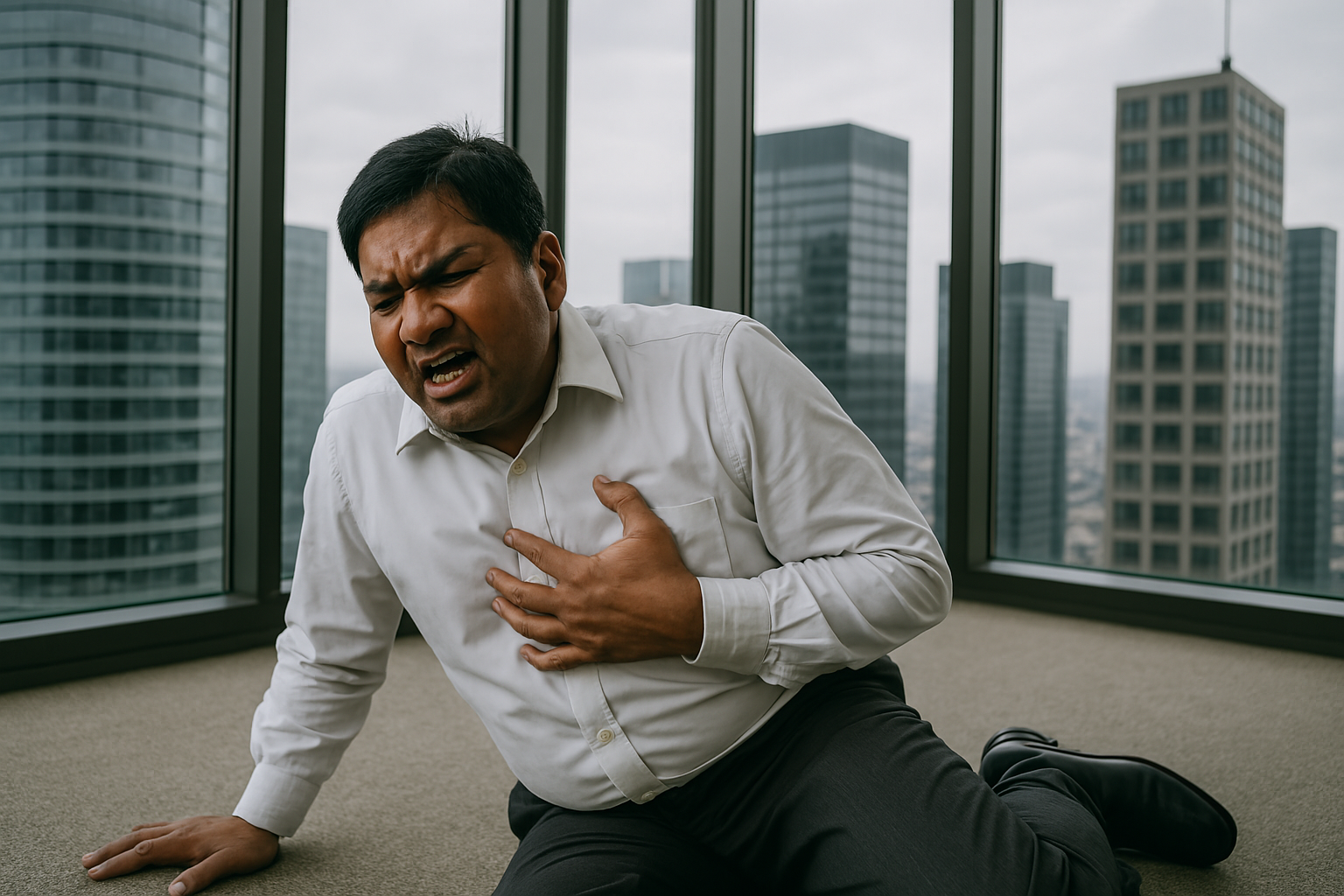

Admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) is associated with a small increased risk of future suicide or self-harm after discharge compared with non-ICU hospital admissions, finds a study published in The BMJ today.

The findings are particularly relevant during the covid-19 pandemic, as the number of ICU admissions around the world reaches all-time highs.

The findings show that survivors of critical illness who later died by suicide or had self-harm events tended to be younger with a history of psychiatric illness, and had received invasive life support.

The researchers stress that the overall risk is still very low, but say knowledge of these factors “might allow for earlier intervention to potentially reduce this important public health problem.”

Survival after critical illness is associated with important effects, including muscle weakness, reduced exercise capacity, fatigue, cognitive impairment, pain, and financial hardship. Growing evidence shows that ICU survivors have higher rates of psychiatric illness, but whether that translates into an increased risk of suicide and self-harm is unknown.

To explore this further, researchers in Canada and the US set out to analyze the association between survival from critical illness and suicide or self-harm after hospital discharge.

Their findings are based on health records for 423,000 adult ICU survivors (average age 62 years, 39% women) in Ontario, Canada from 2009 to 2017.

They matched health records for 423,000 adult ICU survivors (average age 62 years, 39% women) with 3 million non-ICU hospital survivors with similar risk factors for suicide in Ontario, Canada from 2009 to 2017.

Potentially influential factors including age, sex, mental health history, and previous hospitalization for self-harm, were taken into account.

The researchers found that among ICU survivors, 750 patients (0.2%) died by suicide (41 per 100,000 person-years over the study period) compared with 2,427 (0.1%) non-ICU hospital survivors (17 per 100,000 person-years over the study period).

Self-harm was seen in 5,662 (1.3%) ICU survivors (328 per 100,000 person-years over the study period) compared with 24,411 (0.8%) non-ICU hospital survivors (177 per 100,000 person-years during the study period).

Overall, the analysis showed that ICU survivors had a 22% higher risk of suicide compared with non-ICU hospital survivors and a 15% higher risk of self-harm. This increased risk was evident almost immediately after hospital discharge and persisted for years afterward.

Among the ICU survivors, the highest rates of suicide were seen in younger patients (ages 18-34), those with pre-existing diagnoses of depression, anxiety or PTSD, and those who received invasive procedures such as mechanical ventilation or mechanical blood filtration due to kidney failure in the ICU.

This is a large study involving a cohort of consecutive ICU survivors from an entire population, with minimal missing data. However, given the observational design, the researchers cannot rule out the possibility that other unmeasured factors may have affected their results, and say these associations require further study.

“Survivors of critical illness have increased risk of suicide and self-harm, and these outcomes were associated with pre-existing psychiatric illness and receipt of invasive life support,” they write.

“Knowledge of these prognostic factors might allow for earlier intervention to potentially reduce this important public health problem,” they conclude.

Overall risk still very low, but findings could help identify those at greatest risk

Overall risk still very low, but findings could help identify those at greatest risk

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)