Since these are manmade barriers, it is we who have to unmake them if we are to walk the talk on the promise to end TB and deliver on sustainable development ‘where no one is left behind’. There is no other choice because it is a human rights imperative to end TB and deliver on #HealthForAll and #SDGs. And there is no excuse for inaction as clock is ticking: Only 21 months left to end TB in India, and 81 months left to end TB globally (by 2030).

Like justice, health is never given, it is won.

“Like justice, health is never given, it is won,” said a media release by United Nations joint programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) on International Women’s Day.

But if justice and equality can become centre-stage in our world – from the point-of-view of the least served, least represented and least visible communities – and if they are served first with respect and equity, then perhaps we can avert a social uprising to get a just access to health and development for everyone. But then this is a big ‘but’!

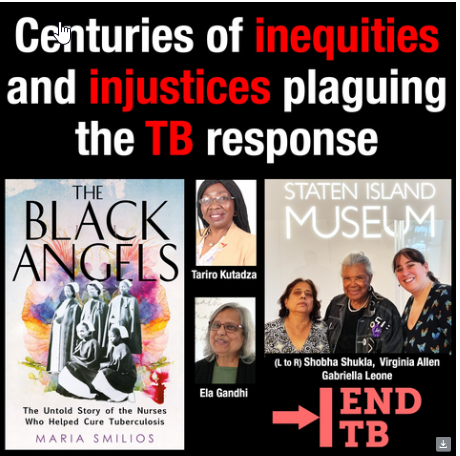

“We have allowed inequities to mar the TB response,” said Dr Lucica Ditiu, Executive Director of Stop TB Partnership. Old TB guidelines of the past years will show how drug-resistant TB, or TB in children were on the blindspot in the Global South. Even data of TB in children for example has started coming forward from high TB burden nations only since the past decade. But richer nations of the Global North were diagnosing and treating drug-resistant TB, TB in children or extrapulmonary TB (TB of body parts other than lungs). “We cannot have double standards,” rightly said Dr Lucica Ditiu, who was speaking at the 2024 World Social Forum (WSF 2024) in Nepal. Since Dr Ditiu has taken charge of the global Stop TB Partnership in Geneva in 2011, TB guidelines are uniform for rich and poor nations alike.

Listen to the ones we serve

But are we finding TB, treating TB and preventing TB everywhere with the best of tools science has gifted us? Why is 140+ years old microscopy still being used in high TB burden nations to screen and diagnose TB? Why are older, longer, less effective, more toxic treatment regimens still being used? Why is TB prevention on the backseat?

Preventing people with latent TB from progressing to active TB disease is possible with the best of available treatments and complemented with nutrition, along with ending tobacco and alcohol, and preventing diabetes, other non-communicable diseases, hunger, poverty, HIV, and a range of other TB risk factors. Are governments not committed to deliver on addressing these TB risk factors, alongside ending TB by 2030 (as they have promised)?

“We must secure the same equitable access to TB care services for everybody. We cannot do this equitably and justly unless we create the processes and systems to embrace everybody by listening to the ones we serve,” said Dr Lucica Ditiu at WSF 2024.

Why is A missing in development?

Is it not high time to set (A)ccountability if even one TB death is a death too many? Despite having highly accurate tests to diagnose TB early (such as molecular tests recommended by the World Health Organization – WHO), shorter and more effective treatments (1 month regimen for latent TB, 4 months for drug-sensitive TB, and 6 months for drug-resistant TB), and scientific evidence-backed know-how to prevent TB, who is responsible for at least 10.6 million people who suffered from TB disease globally in 2022, out of which 1.3 million died?

Science has gifted us tools to test, treat and prevent TB but are we using them?

“Science has never been at fault, but implementation has been lacking,” said Professor (Dr) Rajendra Prasad, Dr BC Roy National Awardee who has made a seminal contribution towards shaping India’s TB response in various capacities since 1976 onwards. He was speaking in the End TB Dialogues hosted by CNS at the 78th National Conference of Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases (NATCON), in Thrissur, Kerala.

Richer nations, like Australia for example, were able to deploy age-old tools in 1960s-1970s to screen everyone and find all TB, treat all TB and prevent all TB. The rate of TB in some of the richer nations is already at the much sought after elimination levels. Then why was it not replicated to fight TB in the rest of the world?

Sumit Mitra, President of Molbio Diagnostics and a thought leader on point-of-care and point-of-need diagnostics, spoke in the recently concluded World Social Forum 2024 (WSF 2024). He wondered that when less than a quarter of the world’s population lives in the Global North (richer nations) then why do those in the Global North have decision-making powers when it comes to global health – especially when health challenges are way more profound in the Global South?

What works really well in the Global North may not work well in the South. Health technologies conceived, designed, and manufactured in the Global North, and funded mostly by the Global North, are being rolled out in the Global South in a way those sitting in the North decide, said Mitra.

“I have every right to demand the best possible diagnosis and treatment. Just because someone is born in the Global North, her/ his/ their right to a healthy life is not in any way higher than mine,” added Mitra.

There are inequities and injustices within richer nations too. But global health challenges in the Global South are so predominant and deadly that they are thwarting health security and sustainable development.

The deadly divide in 2024

WHO’s highest level initiative Find.Treat.All - backed by Stop TB Partnership and others (first launched in 2018), calls upon all countries to replace a TB test (microscopy which underperforms in diagnosing TB) 100% with WHO recommended highly accurate molecular tests by 2027. But only 47% of those with TB disease got a molecular test diagnosis in 2022 as per the WHO Global TB Report 2023. If we use a bad test that underperforms in diagnosing TB (like microscopy) we will miss TB even among those who take that test. These people who are not accurately and timely diagnosed suffer unnecessarily due to TB, as well as the infection keeps spreading from one person to another. Making upfront molecular test diagnosis is an essential cog-in-the-wheel to finding all TB - and entrygate to TB care pathway.

Addressing human-made inequities that jeopardise access to TB care services remains a critical bottleneck. We are failing to ‘reach the unreached’ – at least one-third of the estimated people with TB globally are not notified to TB programmes (we do not know how, if at all, they get a TB test or treatment or any other care or support). Walking the talk on what Mitra and Dr Ditiu have said - to end inequities in global health – is key. Let us take the best of existing TB services equitably to the communities (and closer to the people) in high TB burden settings with dignity and respect.

Linking all those diagnosed with effective and best of WHO recommended treatments is vital.

Antimicrobial resistance is among top-10 global health threats

When it comes to treatment, we have to ensure that a person is being treated with a regimen of medicines to which her/ his/ their TB bacteria is not resistant to. This is possible with a test called drug susceptibility test (DST). Those who get upfront molecular test for TB also can know if they are resistant to one (or few) of the medicines. Not doing upfront DST before initiating the treatment is clinical malpractice, had said Dr Mario Raviglione over 10 years ago to CNS. He was the Director of the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme for almost 1.5 decades. Now, Dr Raviglione is a Professor of Global Health at the University of Milan, Italy, and founding director of the Centre for Multidisciplinary Research on Health Science. He is also an honorary Professor in Queen Mary University London.

Dr Raviglione commented on a LinkedIn post recently: “Indeed, if it [not doing upfront DST] were malpractice 10 years ago in the first years of the era of rapid molecular testing for TB and drug resistance, today it is a crime. Who would ever treat any life-threatening infectious disease without DST in 2024?"

“The acceleration of doing upfront DST we thought would happen when the new End TB strategy was endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 2014. But it did not become a reality due to many factors, including, but not limited to, COVID-19. Even before it, there was no acceleration in decline of TB incidence and death despite high-level political events. Evidently, we need much more on commitment, persistence and research investments. We are all simply not doing enough to address TB-specific challenges, broader health service and system weaknesses, and social determinants of diseases of poverty. At this pace, TB elimination will remain a dream of a few visionary people, while ‘the youth grow pale and spectre-thin and die.’ In the end it comes down to political will at the highest level. Where this will was present results were quick: think about the dozen antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) and rapid HIV diagnostics available and the COVID-19 vaccine. In TB we need exactly the same approach. Citizens are the ones that can make it happen if they just speak louder and keep acting!”, said Dr Raviglione.

Why are 1/4/6 regimens not a reality for everyone in need?

Today we have the best of treatment regimens that can treat latent TB in 1 month, drug-sensitive TB in 4 months, and drug-resistant TB in 6 months. All of these are all-oral treatment regimens, and they are also far more effective and less toxic than the earlier ones. And yet, ALL people in high TB burden nations are not able to access them.

“My dream is to have one treatment to treat all forms of TB – be it drug sensitive or drug-resistant,” says Professor (Dr) Rajendra Prasad who has served the TB response for over 50 years.

End the deadly divide between ‘what we know’ and ‘what we do’

Science has told us what works best to find all TB, treat all TB and prevent all TB. But the reality on the ground is very different at times than ‘what we know is best to do’. We need to end this gap and find all TB, treat all TB and stop the spread of infection – at the earliest.

It is not natural disasters (like hurricanes or storms) which block access to TB care services most times, but manmade barriers that fuel injustices, inequities, greed, and risk factors that put people at risk of TB disease and death.

It is not natural disasters (like hurricanes or storms) which block access to TB care services most times, but manmade barriers that fuel injustices, inequities, greed, and risk factors that put people at risk of TB disease and death.

.jpeg)

.jpg)