For decades, kidney transplants were not seen as a viable option for individuals living with HIV, especially due to historical misconceptions and safety concerns. However, recent studies have turned the tide, presenting ground-breaking evidence that organ transplants between HIV-positive individuals may be both safe and effective. This advancement provides an incredible ray of hope for those battling end-stage kidney disease, especially in countries with long transplant waitlists.

One of the major studies fuelling this shift was conducted by the renowned Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, with funding from the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH). Published in the respected New England Journal of Medicine, the study highlights that kidney transplants between HIV-positive donors and recipients show outcomes comparable to traditional transplants, effectively changing the landscape of transplant options for HIV-positive patients.

The study recruited 198 adults who were not only dealing with the debilitating effects of end-stage kidney disease but were also living with HIV. Participants came from 26 different medical centres across the United States, all offering specialized care. Divided into two groups, 99 patients received kidneys from HIV-positive donors, while the remaining 99 received organs from HIV-negative donors. Over the span of three years, researchers closely monitored several critical factors including overall survival rates, graft (kidney) survival, and instances of organ rejection.

The results, in short, were a revelation: survival rates and kidney function were nearly identical between the two groups, with no significant increase in complications among recipients of HIV-positive organs. This evidence supports the feasibility of HIV-positive organ donations on a larger scale, laying the groundwork for future practices that could change countless lives.

Kidney disease is a common condition among individuals with HIV due to the virus itself, side effects from long-term antiretroviral therapy, and other related health issues. Without access to timely kidney transplants, many patients face extremely limited options. Historically, the few who were eligible for transplants were often placed far behind in priority due to concerns about transplant risks.

Each year, kidney disease reaches a terminal stage for many people living with HIV, pushing them toward dialysis or prolonged hospital stays that further strain their health. Even with dialysis, the chances of long-term survival are much slimmer for these individuals than for those who receive transplants. Adding to this challenge is the sheer shortage of available organs, leaving countless individuals on waitlists with little hope of receiving a timely transplant.

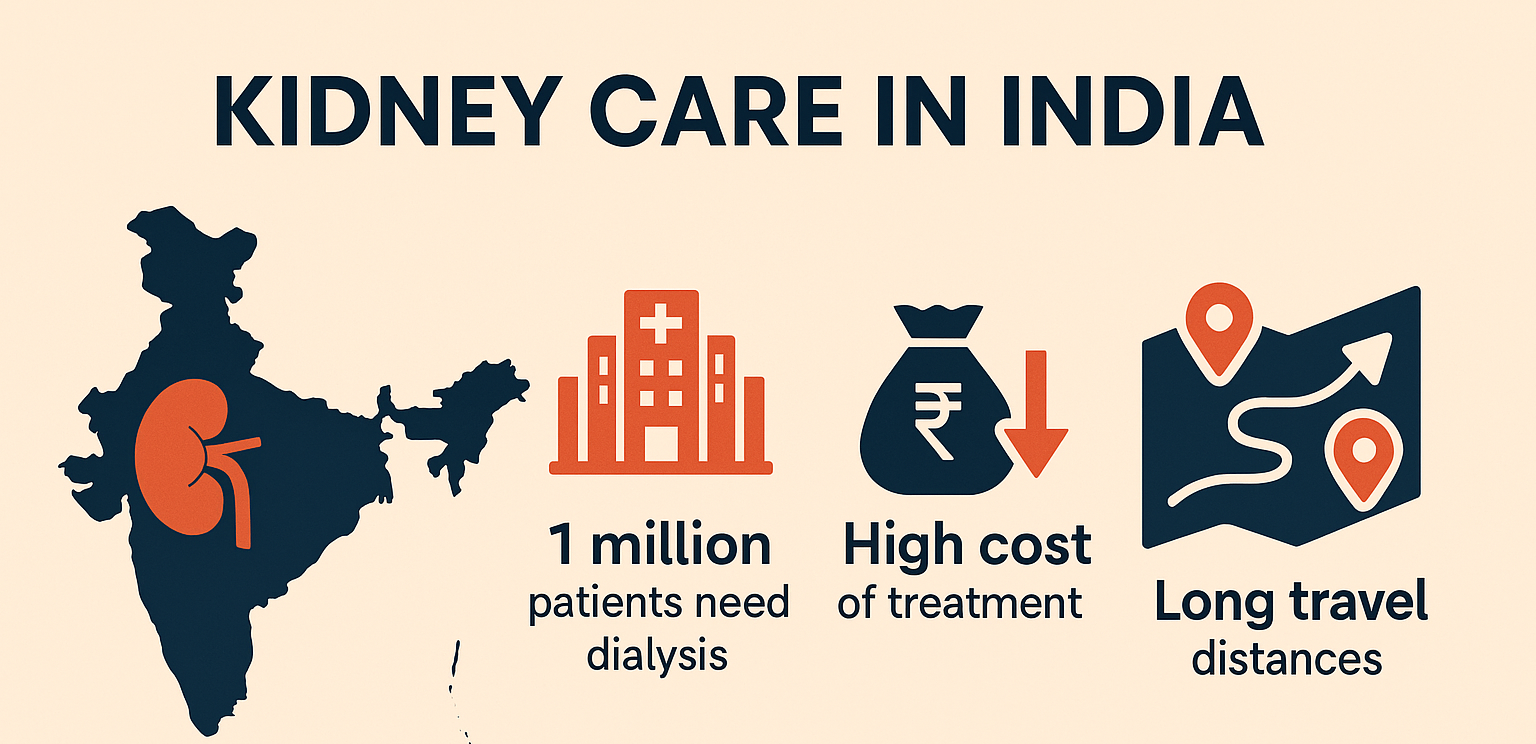

The disparity is stark in India, where estimates suggest that around 180,000 people develop renal failure each year, yet only a fraction (around 6,000) actually receive kidney transplants. Dr. Suriraju V., a senior urologist in India, emphasizes the importance of these recent findings, particularly for a country where demand far outweighs supply. If organ transplants between HIV-positive individuals become widely accepted, it could be transformative, potentially saving thousands who would otherwise face a lifelong struggle for survival.

In response to the need for expanded transplant options, the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act was passed in the United States in 2015. This act legalized kidney transplants between HIV-positive individuals, but only under research protocols to ensure safety. The act set a precedent, pushing for more inclusive policies and allowing HIV-positive patients greater access to life-saving procedures.

The findings from the NIH-backed study offer a powerful endorsement for the HOPE Act. With data now supporting the safety and effectiveness of these procedures, more institutions may feel encouraged to consider organ transplants from HIV-positive donors for their patients. Moreover, researchers believe that global adoption of such policies could lead to major advances in patient outcomes and access.

The study’s data showcases the success of kidney transplants for HIV-positive individuals. One-year post-transplant, survival rates were remarkably close: 94% for HIV-positive recipients from HIV-positive donors, and 95% for those from HIV-negative donors. By the three-year mark, the rates were 85% and 87%, respectively—an impressively narrow margin.

Another encouraging aspect of the findings relates to graft survival, a critical measure of transplant success. Graft survival was consistent between both groups, standing at 93% one year after the transplant for HIV-positive donor organs and 90% for HIV-negative ones. In other words, the transplanted kidneys performed nearly identically, regardless of the HIV status of the donor.

Interestingly, rejection rates were slightly lower in the group that received organs from HIV-positive donors. Among the HIV-positive donor recipients, rejection rates remained at 13% both one and three years post-transplant. Conversely, those who received organs from HIV-negative donors faced a rejection rate of 21%. Though further studies are needed to explore this disparity, it raises intriguing questions about possible immunological benefits within this unique donor-recipient pairing.

The ripple effects of these findings could be profound. For HIV-positive patients, the possibility of receiving a kidney from an HIV-positive donor means shorter wait times and a better chance of a timely transplant. In turn, this can drastically reduce the physical and emotional toll of being on a waitlist, giving these patients a fighting chance for a healthy and extended life.

Countries like India stand to benefit significantly. A shift in organ transplant policies could allow hospitals to make fuller use of available donors, including those previously excluded due to HIV. This would open up an entirely new pathway for patients in desperate need of a kidney, potentially alleviating some of the burden on an overstressed healthcare system.

Dr. Suriraju hopes that India and other nations may look at this research as a model, adopting policies that would allow for HIV-positive to HIV-positive transplants. Proper regulation and oversight would be essential, of course, but the benefits could be transformative. For countries with staggering numbers of renal patients and limited resources, any expansion of transplant options is a welcome development.

While this study marks a breakthrough, it is only the beginning. Researchers and healthcare providers are now calling for continued exploration into HIV-positive organ transplants, particularly in different populations and healthcare settings. This ongoing research would help establish even firmer protocols for safe and successful transplants, ultimately widening access and reducing any remaining stigma associated with HIV and organ donation.

One important consideration is the need for longer-term studies to assess the durability of these transplants over many years. With data indicating near-equivalent success rates between HIV-positive and HIV-negative transplant pairings, there is a growing sense of optimism. This optimism could translate into more clinics and hospitals adopting similar practices, bringing hope to an even greater number of patients worldwide.

For patients, this research sends an important message: a diagnosis of HIV should not limit their treatment options, especially for life-threatening conditions like kidney disease. The study reaffirms that HIV-positive individuals have the potential to live full and healthy lives, provided they receive timely and equitable medical interventions. With proper guidance, HIV-positive patients can maintain both physical health and mental resilience, knowing that effective solutions are within reach.

Healthcare advocates are also encouraged by the study’s implications, as it pushes for fairer policies and broader inclusion of HIV-positive patients in transplant programs. Advocates believe that knowledge sharing and policy alignment can help dispel outdated views, encouraging medical communities across the globe to consider HIV-positive patients as equally viable candidates for organ transplants.

The NIH-funded study by Johns Hopkins University is a landmark moment in the journey toward medical equality. By proving the viability of HIV-positive to HIV-positive kidney transplants, researchers have provided a lifeline to patients previously overlooked due to their HIV status. This achievement shines a light on how science and progressive policies can come together to create a more inclusive healthcare system, one that does not discriminate based on medical history.

For millions of HIV-positive individuals suffering from kidney disease, the potential for a successful transplant now feels within reach. With further advancements and policy changes, these patients may soon have an option that not only enhances their quality of life but also grants them a longer, healthier future.

Source: IndiaToday

For millions of HIV-positive individuals suffering from kidney disease, the potential for a successful transplant now feels within reach.

For millions of HIV-positive individuals suffering from kidney disease, the potential for a successful transplant now feels within reach.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)