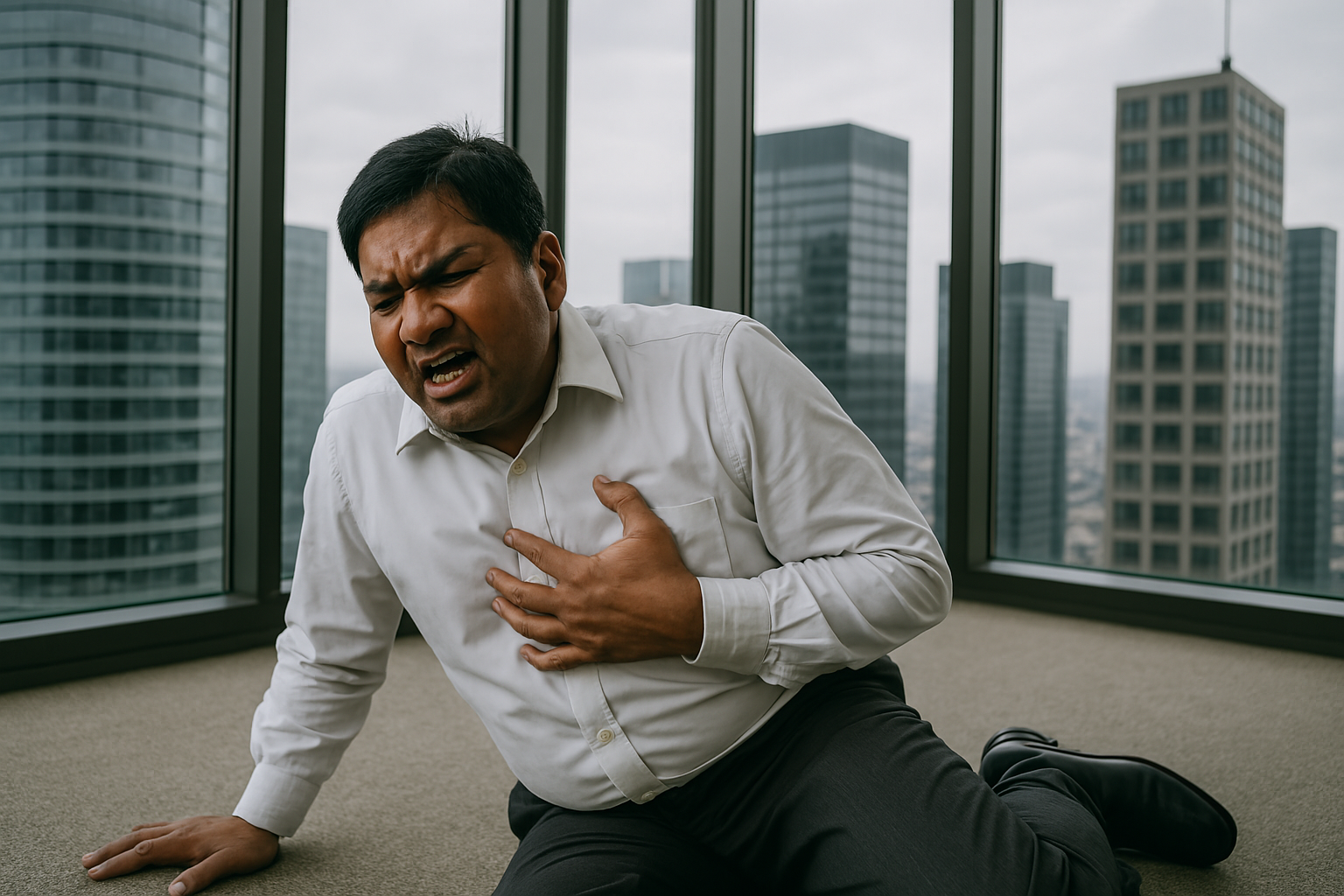

Nearly one in three UK doctors may be ‘burnt out’ and stressed,’ suggests the results of an in-depth survey, published in the online journal BMJ Open.

The findings indicate that doctors working in emergency medicine and genera#l practice are the most at risk of exhaustion, stress, and compassion fatigue.

Whilst only representative of doctors who chose to respond at a specific point in time, the resulting analysis is the largest published study of its kind, drawing on a considerable number of practitioners from a wide range of grades and specialties across the UK, the researchers point out.

Doctors are known to be at higher risk of anxiety, depression, substance misuse and suicide than the general public. They work long hours in highly pressurised, and in the UK at least, frequently under resourced, environments, all of which can take their toll on mental health.

The researchers wanted to find out how resilient doctors across the UK are and how well they cope with the pressures they face, as well as prevailing levels of stress and burnout in the profession.

They drew on the responses of UK doctors to an online survey, distributed through medical royal colleges and other professional bodies, throughout October and November 2018.

The survey specifically measured resilience; professional quality of life (burnout, work-related trauma (stress), and compassion fatigue); and coping mechanisms, using validated scales.

ll, 1651 doctors from a wide range of grades and specialties completed the survey. Some 1518 answered questions on resilience, 1423 responded to questions about professional quality of life; and 1382 answered questions on coping mechanisms.

Analysis of the responses revealed that the average resilience score among respondents was 65, which is lower than other published studies have indicated.

Some differences in scores emerged among grades, specialties, and geography. Hospital doctors scored higher for resilience than general practitioners (GPs), while doctors in surgical specialties scored higher than their non-surgical colleagues.

And recently qualified doctors (foundation years) and specialty and associate specialist (SAS) grade doctors scored lower than specialist trainee doctors and consultants.

Doctors working in Northern Ireland scored higher for resilience than their colleagues elsewhere in the UK.

The scores for burnout and stress were significantly higher than average scores: nearly one in three (31.5%) respondents had high levels of burnout, whilst one in four (26%) had high levels of stress.

Just under a third (31%) scored low for compassion satisfaction - the pleasure derived from being able to help others and from doing a job well - meaning they had compassion fatigue.

Doctors from emergency medicine were significantly more burnt out than those from other specialties and they also registered the highest scores for stress.

GPs had the lowest scores for compassion satisfaction, while doctors from non-surgical specialties had more compassion fatigue than those from surgical specialties.

Ideally, doctors should score low for burnout and stress and high for compassion satisfaction, say the researchers. But this applied to only 87 (6%) respondent doctors.

And nearly one in 10 (120; 8%) scored high for burnout and stress, and low for compassion satisfaction.

The most frequently cited coping mechanisms were distraction from a problem or stressor, or self-blame, rather than thinking about/planning how to deal with a situation, indicating that doctors were not adjusting well to pressures (maladaptive behaviours).

Doctors in Northern Ireland were significantly more likely to draw on religious belief to help them cope than their peers elsewhere in the UK.

This is an observational study, and as such, can’t establish cause. Those already under stress might have been more likely to take part, and many more women than men responded, so the findings may not be representative of the profession as a whole, caution the researchers.

Nevertheless, it is the largest published study of its kind, and the first time that resilience and other psychological factors have been measured in NHS doctors working in the UK, they point out.

Although emotional resilience training is a much favoured tactic to ward off burnout, the researchers question its effectiveness, arguing that it makes doctors solely responsible for their own wellbeing.

“Doctors cannot be expected to recover from the emotional stress and adversity they encounter in their role as clinicians while managing a heavy workload in an under-funded, over-worked system,” they write.

“It is unlikely that emotional resilience is all that is required to cope with increasing regulation, litigation, and administration.”

Nearly one in three UK doctors may be ‘burnt out’ and stressed,’ suggests the results of an in-depth survey, published in the online journal BMJ Open.

Nearly one in three UK doctors may be ‘burnt out’ and stressed,’ suggests the results of an in-depth survey, published in the online journal BMJ Open.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)