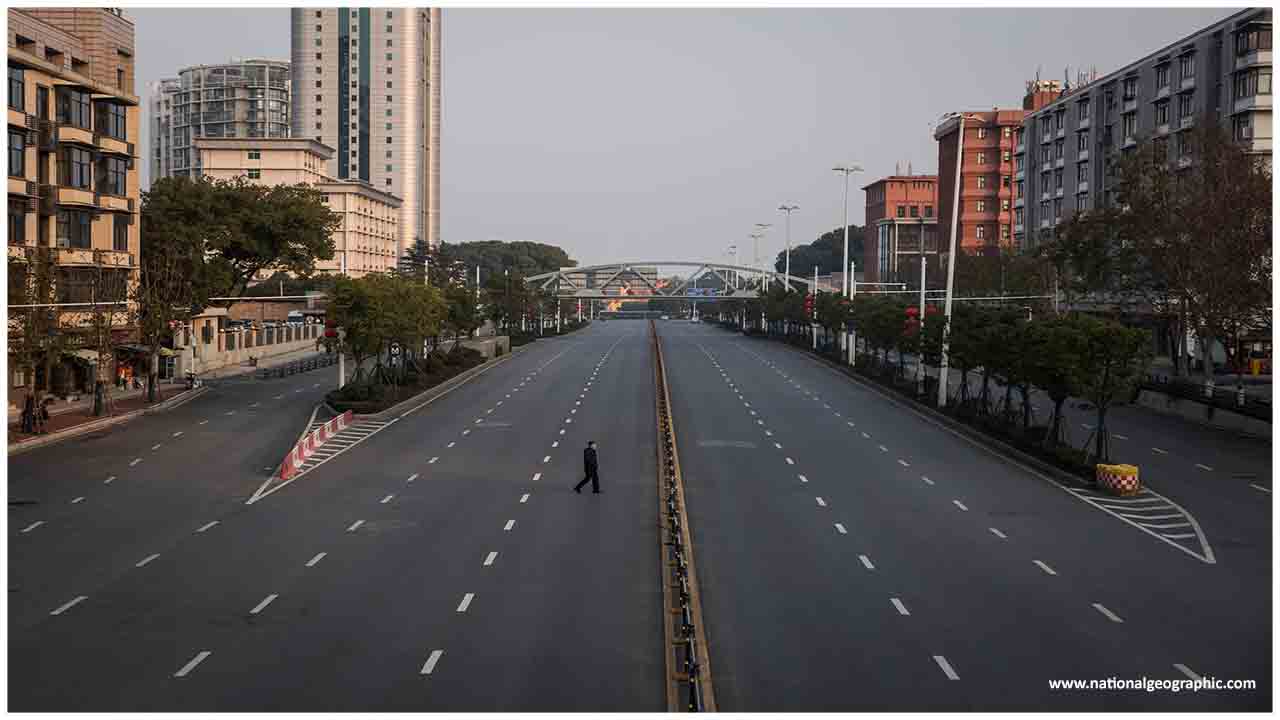

The Chinese city of Wuhan, where the novel coronavirus flare-up first developed, found no new instances of COVID-19 and 300 asymptomatic transporters in the wake of testing a large portion of its 11 million occupants, city authorities said on Tuesday.

Specialists propelled the aggressive, city-wide testing effort on May 14, and contacted 9.9 million individuals, after a group of new cases raised feelings of trepidation of the second influx of contaminations.

In any case, they found no new instances of COVID-19, the sickness brought about by the coronavirus in the crusade, that ran until June 1, authorities told columnists in a preparation.

They said the asymptomatic transporters had been seen not as irresistible, without any hints of infection distinguished on things utilized by the 300 individuals, for example, covers, toothbrushes, and telephones, or on entryway handles and lift catches they contacted.

China doesn't check asymptomatic bearers - individuals who are tainted with the infection yet don't show indications of the illness - as affirmed cases.

The focal city, the capital of Hubei territory, was put under lockdown on Jan. 23. It was lifted on April 8.

It was the hardest hit of any Chinese city and records for most of the 4,634 passings and aggregate of 83,022 diseases revealed in terrain China.

The expense of the city-wide testing exertion was around 900 million yuan ($126 million)

All through January, the World Health Organization openly applauded China for what it called a fast reaction to the new coronavirus. It over and again expressed gratitude toward the Chinese government for sharing the hereditary guide of the infection "promptly," and said its work and promise to straightforwardness were "extremely great, and stunning."

In any case, in the background, it was a very different story, one of the huge deferrals by China and extensive dissatisfaction among WHO authorities over not getting the data they expected to battle the spread of the destructive infection, The Associated Press has found.

In spite of the applauses, China, in reality, sat on discharging the hereditary guide, or genome, of the infection for over seven days after three distinctive government labs had completely decoded the data. Tight controls on data and rivalry inside the Chinese general wellbeing framework were to be faulted, as indicated by many meetings and inner archives.

Chinese government labs just discharged the genome after another lab distributed it in front of experts on a virologist site on Jan. 11. And, after it's all said and done, China slowed down for at any rate fourteen days more on giving WHO nitty-gritty information on patients and cases, as per chronicles of inner gatherings held by the U.N. wellbeing organization through January — all when the flare-up ostensibly may have been significantly eased bac

Authorities launched the ambitious, city-wide testing campaign, and reached 9.9 million people after new cases raised fears of a second wave of infections.

Authorities launched the ambitious, city-wide testing campaign, and reached 9.9 million people after new cases raised fears of a second wave of infections.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)