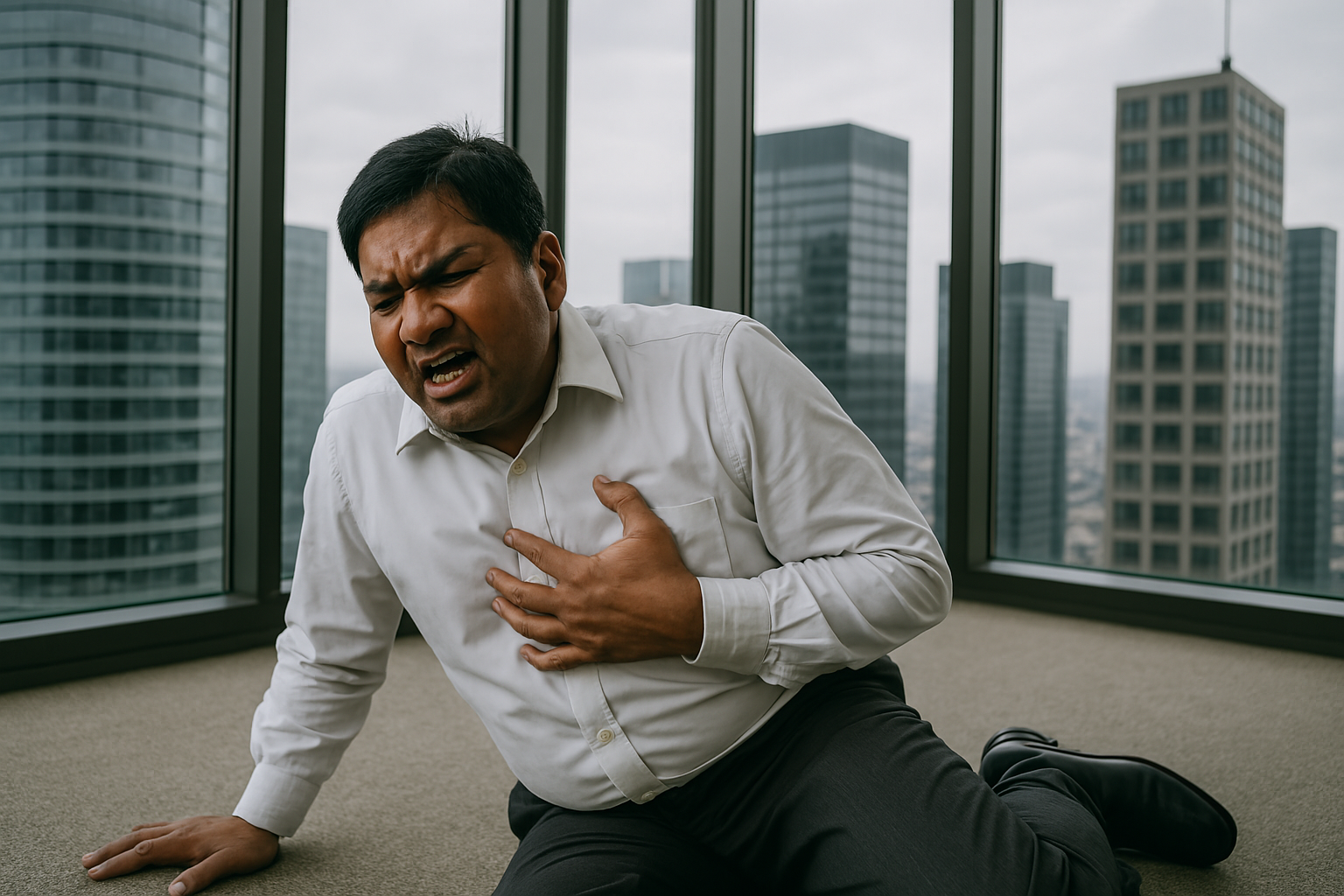

The health benefits of multivitamin/mineral supplements may be all in the minds of those who take them, prompted by positive expectations of effectiveness rather than hard evidence of that, suggests research published in the online journal BMJ Open.

Multivitamin/mineral supplements are widely used, with some estimates indicating that one in three Americans alone takes them regularly: the industry is worth billions of dollars.

Yet a succession of clinical trials has failed to identify clinically measurable health benefits associated with daily consumption among those without known vitamin or mineral deficiencies, say the researchers.

To explore this further, they compared self-reported and clinically measurable health outcomes among users and non-users of multivitamin/mineral supplements.

They drew on information supplied by a large, nationally representative sample of 21,603 US adults, all of whom had been additionally quizzed about their use of complementary medicine in the 2012 annual National Health Interview Survey.

The researchers compiled five psychological, physical, and functional health outcomes from the questions asked.

These were: subjective assessment of health; need for help with routine daily activities; history of 10 long term conditions, such as high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, and arthritis; presence of 19 common health conditions in the preceding 12 months, including infections, memory loss, neurological and musculoskeletal problems; and degree of psychological distress, measured on a validated scale (K6).

Some 4933 respondents said they regularly took multivitamin/mineral supplements; 16670 respondents said they didn’t.

Regular users were significantly older and had higher household incomes than those who didn’t take multivitamin/mineral supplements. They were also more likely to be women, a college graduate, married, and to have health insurance.

Regular multivitamin/mineral supplement users reported 30% better overall health than those who didn’t take them. But there was no difference between those who did and didn’t take them in any of the five psychological, physical or functional health outcomes assessed.

Further in-depth analysis revealed that regularly taking multivitamin/mineral supplements was associated with better self-reported overall health across all race, sex, and education groups, as well as in the under 65s and those on low household incomes.

This is an observational study, and so can’t prove a causal relationship between use of multivitamin/mineral supplements and subjectively assessed health. What’s more, subjectively assessed health is not always reliable, and the researchers didn’t track changes in health before and after taking supplements over the long term.

Nevertheless, the lack of any difference in the health outcomes assessed is in line with other studies indicating that multivitamin/mineral supplements don’t improve overall health in the general adult population, say the researchers.

They put forward two possible explanations for their findings: either regular users of these supplements simply believe they work and that they confer health benefits in the absence of hard evidence to that effect, or they are just inherently more positive about their personal health, irrespective of their supplement use.

A growing body of evidence implicates the power of positive thinking in the improvement of various health conditions, the researchers point out.

“The effect of positive expectations in [those who take multivitamin/mineral supplements] is made even stronger when one considers that the majority of [them] are sold to the so-called ‘worried-well’,” they say.

“The multibillion-dollar nature of the nutritional supplement industry means that understanding the determinants of widespread [multivitamin/mineral] use has significant medical and financial consequences,” they point out.

No measurable clinical improvements between them and non-users, research suggests

No measurable clinical improvements between them and non-users, research suggests

.png)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)