For years, a toxic combination of opioids has quietly fueled an addiction crisis in parts of West Africa. The culprits? Tapentadol and Carisoprodol, two potent drugs manufactured in India and smuggled across borders, wreaking havoc on vulnerable populations. Now, after a shocking exposé, India’s Ministry of Health has been forced to act, swiftly banning the manufacturing and export of this lethal duo. But why did it take international pressure to stop what should have never been allowed in the first place?

This is not just another drug crackdown. It is a story of regulatory failure, pharmaceutical greed, and a government playing catch-up with a crisis that had already spiraled out of control.

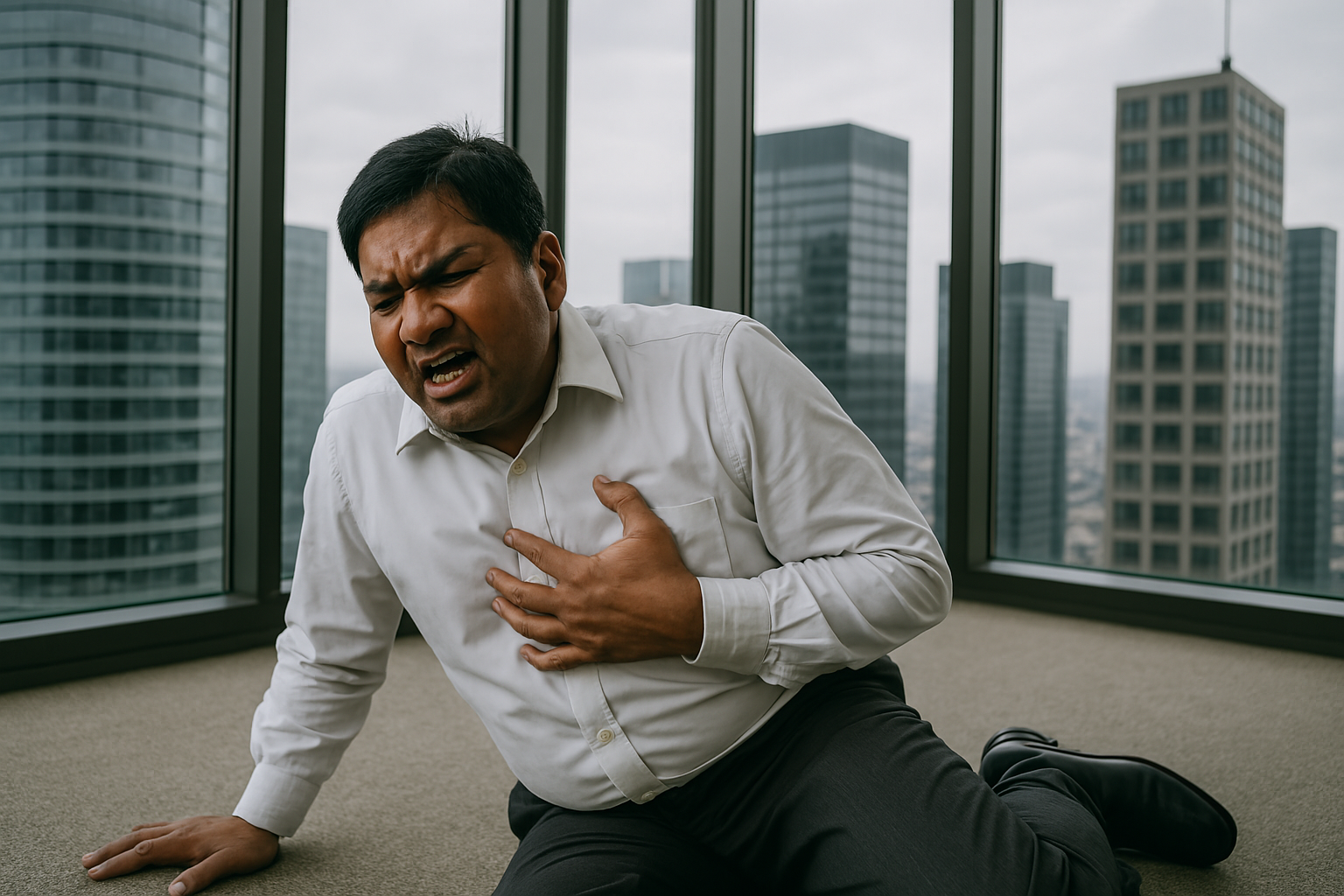

At the heart of this crisis is a powerful combination: Tapentadol, an opioid painkiller, and Carisoprodol, a muscle relaxant notorious for its addictive properties. While Tapentadol is legally prescribed for severe pain management, Carisoprodol has been banned in Europe due to its high potential for abuse. Together, they create a dangerously addictive mix that has led to widespread misuse, particularly in West African nations like Ghana, Nigeria, and Côte d'Ivoire.

This combination, marketed as a quick fix for pain relief, has instead driven people into a cycle of addiction. It suppresses breathing, induces euphoria, and in high doses, can cause seizures or fatal overdoses. Yet, despite these risks, Indian pharmaceutical companies have been producing and exporting these drugs at an alarming scale, until now.

India is one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers, exporting medicines to over 200 countries. However, with great production capacity comes great responsibility. In this case, that responsibility was neglected.

A recent investigation revealed that Aveo Pharmaceuticals, a Mumbai-based drug manufacturer, along with its sister company Westfin International, had been illegally shipping millions of Tapentadol-Carisoprodol tablets to West African countries. These drugs, banned or strictly regulated in many parts of the world, found a thriving underground market in places where law enforcement is weak, and healthcare infrastructure is inadequate.

Shockingly, these shipments continued despite the well-documented dangers of these drugs. It took a BBC exposé to bring the issue into the spotlight, forcing Indian regulators to take action.

After the revelation, India’s Drugs Controller General, Dr. Rajeev Singh Raghuvanshi, moved quickly to revoke all permissions for the manufacturing and export of the opioid combination. The Ministry of Health also conducted an emergency raid on Aveo Pharmaceuticals Mumbai facility, seizing all stock of the drug. Additionally, all Export No-Objection Certificates (NOCs) were withdrawn, effectively shutting down any further distribution.

But here’s the real question: why was this combination even allowed in the first place?

The risks of Carisoprodol have been well known for years, leading to its ban in the European Union and several other countries. Tapentadol, while useful in pain management, has strict regulations in most developed nations due to its opioid properties. Yet, India’s pharmaceutical industry continued manufacturing and exporting the combination without stringent oversight until it became a global scandal.

A Larger Pattern of Regulatory Lapses?

This case is not an isolated incident. India’s pharmaceutical sector has often been criticized for its lack of strict regulation, particularly concerning the export of controlled substances. The country has faced previous allegations of manufacturing and distributing substandard or harmful drugs, sometimes leading to global recalls and bans.

Several key questions now arise:

Why did Indian authorities fail to act sooner?

Who approved the manufacturing of this combination despite its well-documented risks?

How many other dangerous drugs are slipping through the cracks of India’s regulatory system?

While the recent ban is a necessary step, it highlights a larger need for stricter monitoring of pharmaceutical exports.

The damage done to West African nations will not be undone immediately. These pills have already entrenched themselves in underground drug markets, and addicts suffering from withdrawal symptoms will continue to struggle.

Public health experts warn that simply cutting off the supply does not end an addiction crisis. Governments in affected countries will need to invest in rehabilitation programs, while law enforcement agencies must crack down on the illegal distribution networks still operating.

Additionally, there’s a concern that banning one drug combination might simply push the market toward other dangerous alternatives. The opioid crisis in the West, for example, evolved from prescription painkillers to heroin and synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Will West Africa face a similar fate?

India has a reputation as the “pharmacy of the world,” but with that title comes responsibility. To prevent similar crises in the future, the government must take stronger measures:

1. Strengthening Drug Export Regulations: The export of opioids and other potentially dangerous drugs must undergo stricter scrutiny. A real-time monitoring system should be in place to track shipments and prevent misuse.

2. Blacklisting Companies That Violate Drug Laws: Pharmaceutical firms that engage in illegal exports must face permanent bans, not just temporary suspensions. Stronger penalties, including criminal prosecution, should be enforced.

3. Creating a Special Task Force for Pharma Oversight: A dedicated regulatory task force should be established to monitor the manufacturing and distribution of sensitive pharmaceuticals, ensuring compliance with global safety standards.

4. Increasing Transparency in Drug Approvals: The approval process for drug manufacturing should be more transparent, with a clear public record of approvals and regulatory reviews.

5. International Cooperation to Curb Drug Abuse: India must work closely with affected nations like Nigeria and Ghana to prevent the resurgence of these drugs through new smuggling routes. International partnerships will be crucial in tackling this issue effectively.

The ban on Tapentadol and Carisoprodol is a necessary but delayed move. It exposes deep flaws in India’s pharmaceutical regulation and raises uncomfortable questions about accountability. If India truly wants to be a global leader in healthcare, it cannot afford to wait for international scandals before acting on public health threats.

This incident should serve as a wake-up call for the government and the pharmaceutical industry. Stricter regulations, greater transparency, and proactive enforcement are the only ways to ensure that India’s “pharmacy of the world” reputation is built on trust and safety, not on scandals and cover-ups.

Stricter regulations, greater transparency, and proactive enforcement are the only ways to ensure that India’s “pharmacy of the world” reputation is built on trust and safety, not on scandals and cover-ups.

Stricter regulations, greater transparency, and proactive enforcement are the only ways to ensure that India’s “pharmacy of the world” reputation is built on trust and safety, not on scandals and cover-ups.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)